The London Underground has many strange and weird stories to tell, but one that has almost fallen through the cracks of history is the Station designed by Russian Futurists in 1936. At the beginning of the 1930’s the Soviet Government decided to press ahead with plans for a Moscow Metro system, giving the design contract to do so to Lazar Kagonovich with a brief to include elements of Soviet superiority including the new Russian Futurist art movement, which was appreciated by Stalin as portraying a ‘new era’ of technical design based on an analytical approach and fascination with the dynamism, speed, and restlessness of modern machines and urban life that modern technologies of the day were ushering in.

There was one problem – Kagonovich knew nothing about engineering and even less about tunnelling. He sub-contracted work to a British company, Markham, who had built part of the London Underground, and were a subsidiary of John Brown & Co , the then Devonshire-Ellis family business. John Brown & Co were well known to the Russians – they had previously built two ships as well as turbines towards the end of the Imperial era. Their subsidiary, Markham, were chosen to provide the technical plans for the initial stages of the Moscow Metro comprising 11km and 13 stations. Markham engineers travelled to Moscow to undertake the engineering work, while Soviet engineers went to London to examine and further learn details of how the London Underground – which was still being expanded at that time – operated. Moscow architects meanwhile designed the interiors of the Moscow Metro stations, still famous today.

The original opening of the Moscow Metro was a great success, with the first line opened to the public on 15 May 1935. The day was celebrated as a technological and ideological victory for socialism, while an estimated 285,000 people rode the Metro at its debut. The design was greeted with pride; street celebrations included parades, plays and concerts, including the Bolshoi Theatre presenting a choral performance by 2,200 Metro workers; 55,000 coloured posters (lauding the Metro as the busiest and fastest in the world) and 25,000 copies of “Songs of the Joyous Metro Conquerors” being distributed. This publicity barrage, produced by the Soviet government, stressed the superiority of the Moscow Metro over all other metros in capitalist societies and the Metro’s role as a prototype for the Soviet future. The Moscow Metro averaged 47 km/h (29 mph) and had a top speed of 80 km/h (50 mph). In comparison, the New York City Subway trains averaged a slower 25 miles per hour (40 km/h) and had a top speed of 45 miles per hour (72 km/h). While the celebration was an expression of popular joy it was also an effective propaganda display, legitimizing the Metro and declaring it a success.

The Markham project in Moscow had been a great engineering and mutual design experience, yet further co-operation was banned by the KGB, wary of the British learning any more about the layout of Moscow. However the collaboration has a strange twist. The Russian engineers and designers sent to London to learn and study were given the opportunity to practice on one of the outer most London Underground Stations – Gants Hill, in Ilford, on the Central Line. Accordingly the station interior was designed by Soviet era architects and remains a striking example of Soviet and Russian Futurism Art forms. The station architecture is almost exactly like the Moscow Metro.

Gants Hill London Underground Station

Additionally, as one exits the station, the foot passages are lined with tiling patterns heavily influenced by the Russian Futurism movement, and artists such as Kazimir Malevich in particular, as he had died in St. Petersburg in 1935, the year before the Gants Hill Station was completed.

Gants Hill London Underground Foot Tunnel Tiling

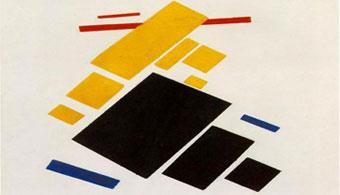

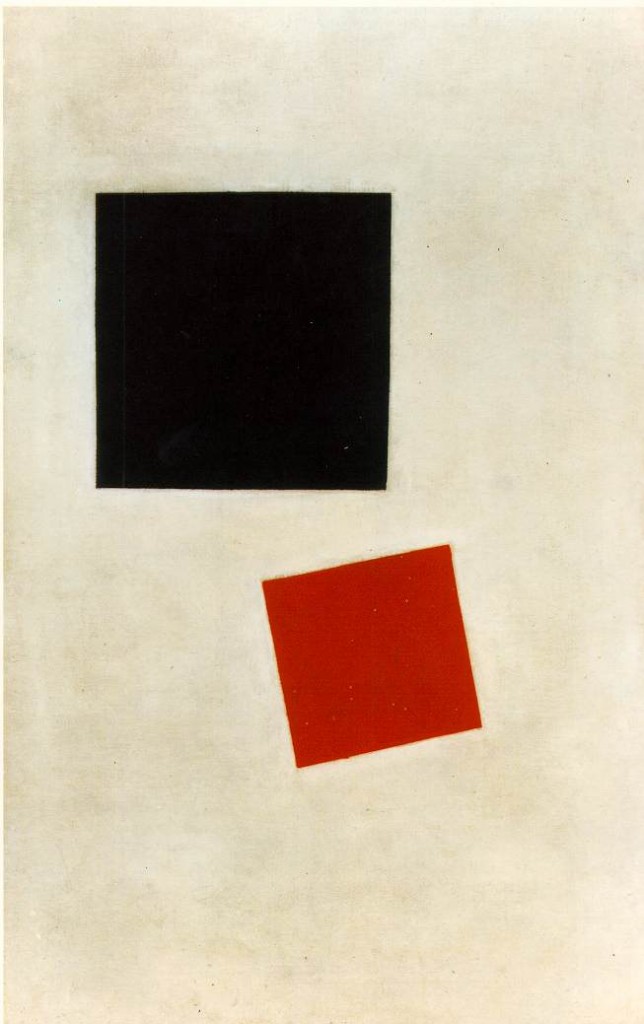

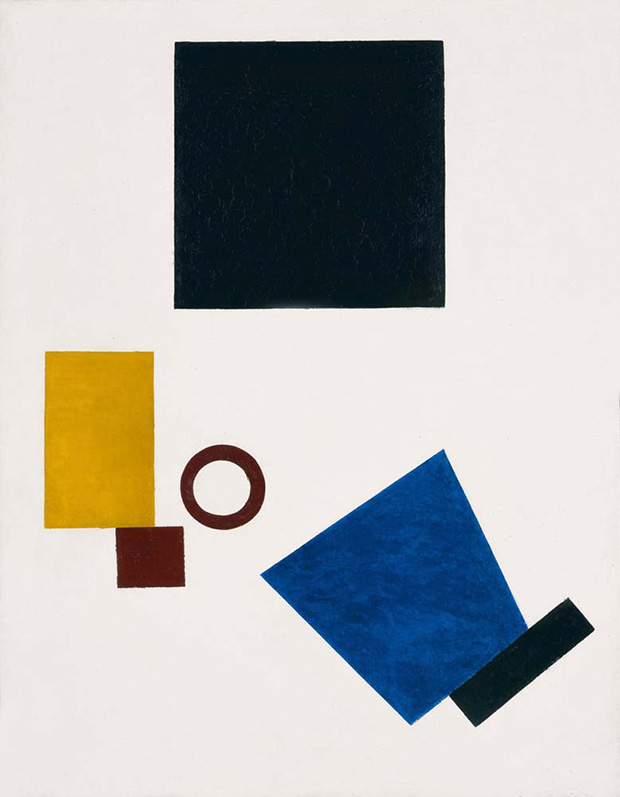

We can compare the design with some of Malevich’s work of the same period.

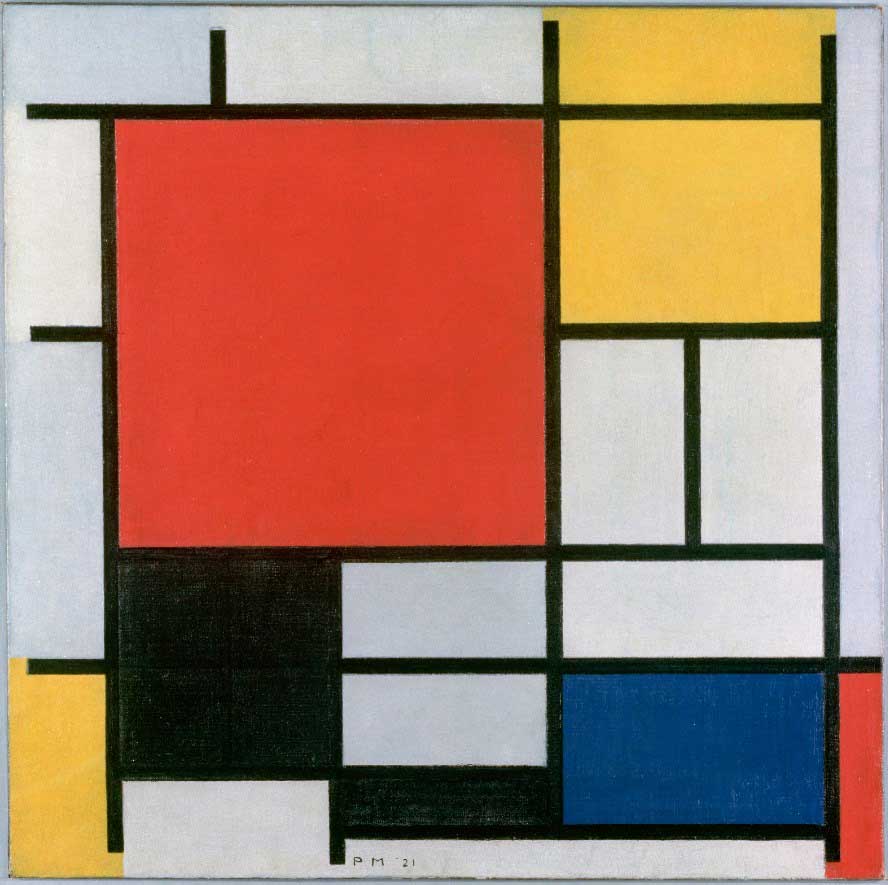

While referenced appears to be made to another Futurist artist of the time, Piet Mondrian, who himself had been heavily influenced by Malevich.

The Gants Hill London Underground Station therefore serves as a defacto Architectural and Russian Futurism time capsule; a little piece of Soviet era Moscow preserved in London. Getting there is a 30 minute ride on the Central Line from Bond Street station, just make sure you take the trains going via Hainault as Gants Hill is on a separate end loop to the main Epping bound trains. The return from Bond Street is 12 Pounds. That’s good value compared to the amount that Malevich’s work sells for at auction. Sothebys recently sold some of his work for over $21 million, making Gants Hill station well worth the pilgrimage to enjoy art and architecture from the Russian Futurism era, circa 1936 for free.