The brothers Ron and Russell Mael, better known as the now, somewhat belatedly acclaimed ‘pop’ – as in popular – group Sparks, have been having somethings of a renaissance – itself something to wonder at as both men are now well into their seventies. That speaks volumes for the sustainability of the creative muse when many men are happy to drift into retirement, and accept their best years were long ago. But not these Gentlemen. Here is a brief career background – it’s been well covered elsewhere, and their ultimate journey back to referencing their Paternal Mother Russia.

Having been a fan since 1974, when famously, they appeared on the British TV show “Top of the Pops” and suddenly transfixed the nation with the bombastic, highly original “This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both of Us”.

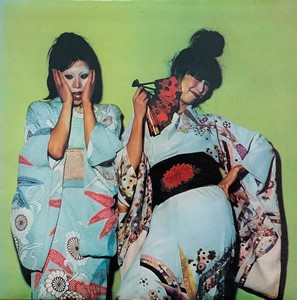

It was a massive hit. Taken from the Japanese Geisha artwork of the subsequent album “Kimono My House” (David Sylvian was also watching) this introduced the concept of art-rock in a new, imaginative style. It was only to last for another album, more of the same in the follow-up “Propaganda”. This pair of albums remain extraordinary statements of manic dark wit coupled with furious arrangements.

They then changed tack, recording an eccentric, yet now well-loved LP with Tony Visconti, David Bowie’s producer. Diminishing returns followed, with a misunderstood Ramones tribute album “Big Beat” following, but missing the punk fury for the pop hooks.

The Maels reinvented themselves yet again – a lesson in never giving up that is pertinent more to the corporate world than yesterday’s artists; and recorded a ground-breaking synth album called “Number One In Heaven” in 1978, that pointed the way ahead for acts as diverse as New Order, Erasure and the Pet Shop Boys, amongst many others. The original inspiration for that though was a pre-1974 Sparks hit, a 1972 song by a group called Chicory Tip, a track called “Son Of My Father”. The producer? A young German electronic keyboards wizard, Giorgio Moroder. France’s biggest selling single of the following year was next.

After this success, the Maels decamped back again to the United States to make it, with varying degrees of success, as a fun LA pop band. A highlight of the time was the single “Cool Places” which charted, but otherwise, the familiar story of similarity crept in. To break that, the Maels did something extremely bold and somewhat unwise. That “Kimono My House” album of several years earlier had proved iconic (in Japan) and following a couple of collaborations with Japanese rock bands (examples here and here) came across the Tokyo Manga tale, “Mai the Psychic Girl”, which had just been published by Virgin books (whose Virgin records label had released their “Heaven” album.

The brothers purchased the film rights, and courtesy of friends of friends (an ex-Sparks drummer had married the Hollywood Producer Tim Burton) spent an astonishing seven years writing the music and trying to get financing for the film. But the project fell through. Seven years wasted…

By this time, in the pop music world, Sparks were all but forgotten. They hadn’t released anything for nearly a decade, their most recent albums prior to this hadn’t sold especially well, and it must have been a devasting thought to feel you’re all washed up – and rejected. So – what do you do?

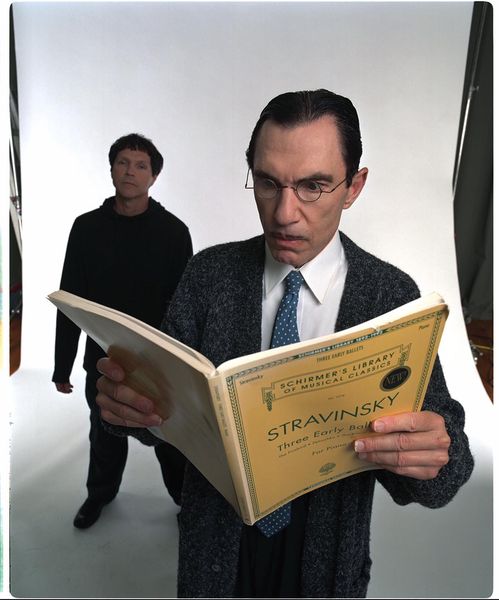

What you do is make a fuck-off killer album as a comeback to reclaim previous territory. This is where the contemporary Sparks period really begins. Updating, and reclaiming the Pet Shop Boys sound (who were not amused), the Maels stormed back. They then decided, after an entertaining orchestrated reprise of their earlier hits, to embrace their inner Russianness. This began, tentatively, with an obscure B-side, again reunited with Tony Visconti, in a track about opera. Ron Mael was even pictured at the time with a Stravinsky score sheet. (The music to that is “Three Early Ballets”, which includes the “The Firebird”, “Petrushka”, and “The Rite Of Spring”). This new direction, looking in the past to gain future inspiration, had a profound effect on the Mael’s creative subconscious.

This evolution took another album. “Balls” (whose title track really ought to be reimagined by Liam Howlett) included a track called “Aeroflot” – Russian, yet still Euro-disco. But it was after this album that Sparks really began to move ahead.

There has been a series of song albums over the past decade that have begun to define who Sparks really are: a very personal process of the Maels aging like fruit-infused vodka, and delivering this bonus both lyrically and sonically. There is a straight, almost flawless run of albums for which I provide a personal selection of tracks, from “Lil Beethoven”, “Hello Young Lovers”, “Strange Animal”, “Hippopotamus”, “A Steady Drip, Drip Drip” (Stravinsky’s Only Hit) and their most recent, “The Girl Is Crying In Her Latte”. with a song about discos in North Korea.

They are shortly to release their seventh in this series.

Meanwhile, here’s the total killer. During this same burst of creativity – with both Maels in their mid-60’s to mid-70’s – they also wrote two operas.

Russian opera in particular, is a favourite of mine. So, what is the difference between Russian opera and say, Italian opera? Much depends on the contributing libretto and its origins. The Russians have a long literary history, reminiscing about long cold winters, poverty, war, class, and death. The Italians, where the weather is rather better, sing about wine, women, illicit affairs, eating, and life.

The point about the Maels is that they write songs about both. This maybe because their Papa was ethnically Russian (apparently his family fled the Bolsheviks) while their Mother was Eastern European (Polish I believe) who fled Hitlers ravages. Yet the brothers grew up in California. There you have the perfect combination; a family background steeped in the Russian (and East European classics of literature and music, and a childhood background of the Beach Boys and Basketball heroes.

This means that within the Mael brothers, a somewhat exclusive combination exists – historically able to look back on ‘foreign’ and American influences, yet with one eye on the future. As men become more experienced – an inevitable (one hopes) attitude to aging, it appears that the Maels, perhaps subconsciously, are also referring to their past. This is why musical references to Prokofiev and Shostakovich’s music crop up in their 2009 opera, “The Seduction of Ingmar Bergman.” Soviet era paranoia is alive and well for example in Ron Mael’s orchestration of tracks such as “Escape”.

That sense, in the plot of their Bergman opera, of feeling alienated in the United States, may well be a reflection of their Father’s original experiences as a Russian emigre in the US. Such themes can be absorbed by sensitive young boys (Ron Mael was born in 1945). Family reminiscences count among influences in a child’s future psyche.

The Maels also – as composers are wont to do – craftily insert references to their own output in these records. The bars of “This Town Ain’t Big Enough” are contained within Annette’s finale, to which are also added subtle lyrics – to a soundtrack marketed as an opera – “It’s getting too operatic for me!”

There’s rather more. Within the Sparks recycling theme – Stravinsky especially used to do the same with his music – are elements of the obscure, original “Big Brass Ring” in the Bergman opus. “Annette” also contains several references to previous Sparks and related songs, including an orchestral refrain from “Les Amants Des Pont Neuf” recorded by Les Rita Mitsouko in 1993 – previous Sparks collaborators – and the finale of Leos Carax’s first film – the director behind 2021’s “Annette.”

Back to Russia, and a just-released song from the original, 2013 version of Annette is called “(I’ve Got A Lot In Common With) Dostoevsky”, while also name-checking Chekov and Tolstoy. Meanwhile, there’s plenty of orchestral conducting in Annette too.

There are two points here. One: Sparks are leaving lots of Easter Eggs around for fans to discover. So go find them! Secondly, contemporary Sparks has distinct references to much Soviet-era Russian music buried within, and that’s fun to find – if you know what to look out for. But take my word for it – there’s a lot of Soviet Russian influences cropping up in Sparks music. Finally, we can end with a dance about all that. Here’s 1977’s “Goofing Off” as a Cossack dance reference. Sparks’ Russian influence is right there. Focused and refined through San Franciscan eyes it may well be – however the family background influences, stories, old memories and experiences as being part of a once removed, yet remembered lost culture are deeply entrenched in what makes Sparks, Sparks, and why the Maels can do what they can do.