Roy Chapman Andrews was a famous explorer and naturalist, who uncovered, as a result of several 1920’s expeditions into the Gobi desert, that dinosaurs laid eggs. He also discovered many new species of dinosaur and helped direct the evolutionary theory that contemporary birds are the evolutionary extension of these prehistoric creatures.

Andrews was certainly charismatic. His numerous books about his adventures were best sellers of the day, while the more recent Indiana Jones film character appears to be based on Chapman’s outdoor style.

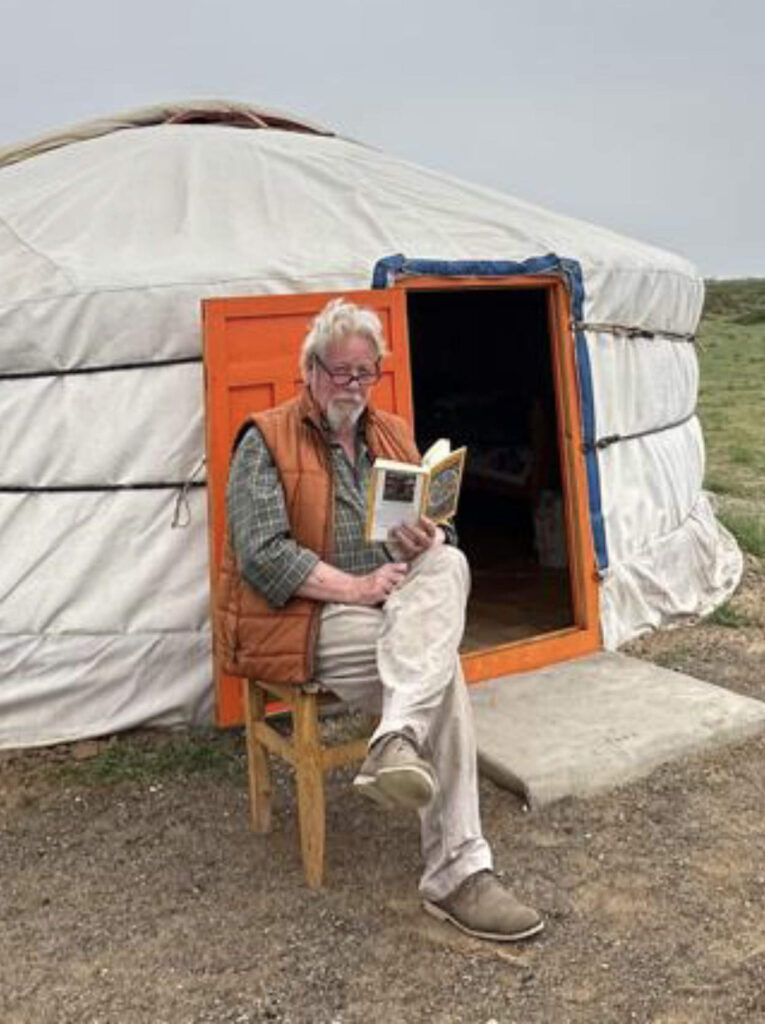

It’s been awhile since I’ve visited Mongolia, although I’ve had an apartment in Ulaan Baatar for many years now – I used to go and hang out there a lot when I was based in Beijing and got fed up with the insularity of many of the expats there at the time. Instead of bored, drunk Europeans and Americans bitching about China and getting drunk in bars, I would have chats with Russian-Mongolian Cossacks and spent my weekends out on my horse. Beijing-Ulaan Baatar is a 90 minute flight. However, covid and other issues have delayed my return – it had been five years since I had visited.

Meeting up with me to help plan my trip was Enkhzul Orgodol, (Zula) who acted as a guide for me in Mongolia over 20 years ago, once worked for my firm in Singapore, and is now married and a Mother to two large boys. She also runs an educational programme aimed at getting impoverished Mongolian women into the workplace. So for old times sake, we dusted off my Mongolian maps and began planning on my UB apartment dining table…

The trip we planned we see us travel in some style in a Toyota Land Cruiser, staying at Gers along the route. It was time also to send to the dry cleaners all of my outdoor gear – in fact everything in the apartment as five years worth of dust – and moth attacks – had rendered a complete clean up from top to bottom necessary. My washing machine, completely unused to the stress of being used, broke. Once everything was sorted – a five day job and a spic and span apartment, it was time to depart….but not before enjoying a reunion with Zula’s family and a traditional Mongolian Hot Stones BBQ. And that is a story in itself…

Cooking with Mongolian Hot Stones

Out in the Steppe, this is done on a fire, but in the modern world, a single gas powered ring is sufficient. All you need are some round stones about half a kilo in weight each, which are heated up directly on the flames for about 20 minutes. Transfer these to an aluminium pot, and then add chunks of beef / yak or whatever meat you have to hand, together with a selection of vegetables such as carrots, onions and potatoes and anything else to hand. Season, add local herbs (wild chives grow all over Mongolia), add some cumin – and put back on the heat with a little water. Cover with the lid and cook through again for another 30-40 minutes. Serve.

The already hot stones in the pot, and the external heat outside the pot, jointly act to cook the meal through. The result is delicious.

Departure

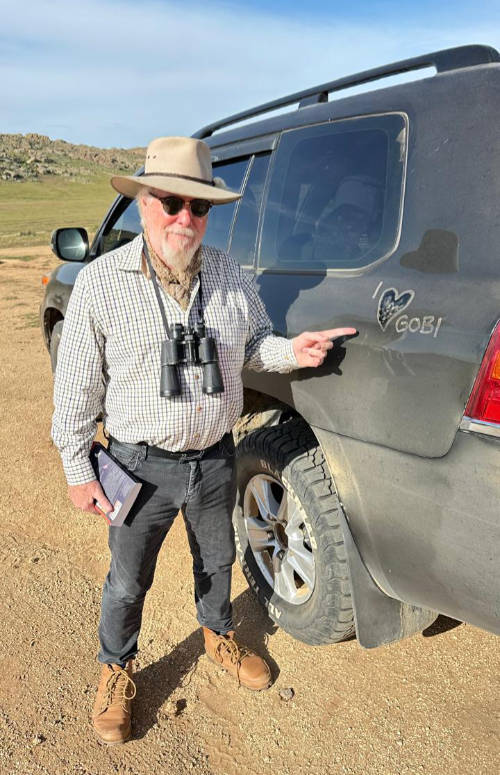

The weather in the Gobi can be unpredictable, and in mid-August warm during the day and chilly at night. Sleeping conditions can be erratic so I always pack sleeping bags and a couple of warm rugs. Its wise to add toilet paper, wet wipes and an antiseptic talcum powder to help with personal hygiene along with the usual essentials – in addition to several large, full water containers. Sun cream, mosquito coils and a baby-safe mosquito spray (for use on your face) are advisable together with a small medical kit including Imodium. Towels, and all the usual essentials such as a torch, and phone / camera chargers. Its preferable if you can charge equipment in the vehicle, so take any adapters necessary. I always take a compass just in case it clouds over, binoculars and a good book for evening reading. And dress appropriately! We left Ulaan Baatar at 7am with our driver Gomba and Guide Handa, Zula’s sister.

Driving South

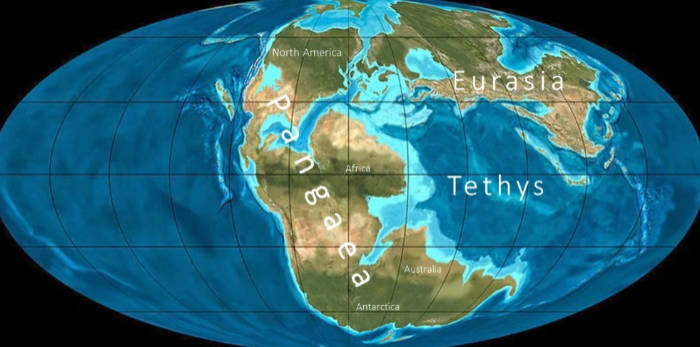

The Mongolians have names for 32 different types of Gobi, with the word itself just meaning “desert”. As we head south, we begin to leave the green steppes, made up mostly of steppe grass, and can see the landscape gradually become increasingly sparse – grasslands give way to tufts of wild chives and aromatic sagebrush and a barren, rocky landscape begins to reveal itself under the plant life. During the prehistoric Mesozoic and early-mid Cenozoic Era – 66 million to 250 million years ago – all this was part of the Tethys Ocean, which reached from what is now the Mediterranean sea, across the Middle East and through Central Asia and way into what is now East Asia. This is why the region is desert – multi-million-year-old sand beds, gravel and smaller rocks, interspersed with occasional rocky outcrops appear similar to the surface of Mars. All this was once a deep ocean seabed, with prehistoric fish and other ancient exotica swimming through the waters above. Pick up a rock here and you’re probably the first human to have ever touched it.

As for much of the sand, created by oceanic waves pounding for millions of years at the ancient coastline, much of it, but not all, has long been dispersed around the world. The winds pick it up and still occasionally create sandstorms, while the contemporary spring weather both across Mongolia and south to China still dumps fine dust and sand onto cities every year. Sand from the Tethy’s sea bed has been found all around the world as ancient winds exported it globally. Now, in Mongolia, most of what is left is basic ground rock. This is another form of Gobi and perhaps the most inhospitable. Yet plants and animals have still managed to adapt and survive.

Mandalgovi

When I was last in Mandalgovi it was literally a one horse town, and very rural. It is sited on a Gobi transition zone of scattered bunch grass which soon lads to the great Gobi desert, about 300 km south of Ulaanbaatar. Mandalgovi has always been a focal point of the South Gobi region, being the capital of Dundgovi Aimag (Province) and acting as a commercial hub for regional nomads, mainly cashmere wool herders. Now it has grown into rather a lot more – it even has a roundabout, a handful of hotels, a few restaurants and a college. That boom has come from the foreign mining companies, with operations all around this area. Fortunately, there doesn’t seem to have been any increase in pollution although nearer the mines the issue may not be too great. It’s also good to see some of that wealth creation filter down to the local communities.

Note that wifi connectivity on these journeys is limited to these towns, so be prepared to go for hours without connections when travelling between them.

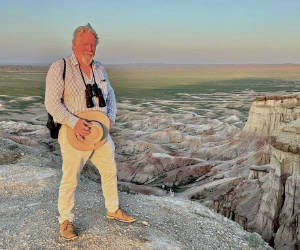

Mandalgovi is a useful stop off, although there’s not a lot in the town. Nearby though are a section of the Flaming Cliffs, giant sandstone ripples rising out of the desert floor. Sunrise and sunset are the best time to visit, with the rocks reflecting the sun’s rays as they spread across the horizon. There are several ‘Flaming Cliffs’ in the Gobi – this one in Mongolian is known as Tsagaan Suvarga – and is one of the sites that Andrews worked at in his dinosaur research.

The so-called ‘White Stupa’ is here, a 2km walk across the cliffs. It is named after a hard sand stone formation created by the winds over millions of years, but it too, will eventually crumble into pieces on the desert floor. Occasionally, that erosion reveals the white fossils of an ancient sea creature, and shards of these can sometimes be found at the base. Such pieces are worthless, as scientific research and dating requires them to be found embedded in the rock to identify the strata and therefore the era. Note it is illegal both to dig or to take pieces away. Departure customs at the airport upon leaving take aa dim view of your having bits of dinosaur in your luggage.

There are several eco-ger camps around, although remember that water is a precious commodity in the Gobi. Note that these only operate from about May-September as otherwise the weather is too harsh. It’s worth noting that the evening skies, this far away are clear of light pollution, and its well worth having a Night Sky app on your phone to track the planets and stars. The views of the Milky Way can be spectacular, and as a tip, it’s well worth setting your alarm for a 3am view if you want to see the best views.

Dalanzadgad

Mongolia’s Aimag capitals now have ‘gateways’ constructed as a sort of official entrance, with Dalanzadgad being the semi official ‘capital of the Gobi’ if there was such a thing. It too has benefited from mining income, and even has a minor ring road to help you navigate. It’s about double the size of Mandalgovi and has an increasingly well used airport with connectivity to Ulaan Baatar. Its pleasant enough, and now even has a new Gobi Museum. It’s worth a trip to see the Dinosaurs, which includes a Tyrannosaurus Baatar – the Asian cousin of the T-Rex.

There is an interesting local minerals section, as well as a display of old Mongolian lives and culture and a contemporary at section. Unless you’re on business here it’s not really worth staying long, and ger camps 15-20km out of Dalanzagad have less light pollution.

Yolin Am

The reason to be here however is Yolin Am – a valley carved out of the Gobi desert floor by a natural fresh water spring. The entrance to Yolin Am – which means ‘Valley of the Lammergeier’ – a type of Vulture – is now rather busy, but there is an interesting, small local natural history museum here with specimens of the type of natural fauna one can see in this area.

It is now possible to drive into the valley until an end point is reached which now has the option of hiring horses to ride deeper into the chasm. I have visited several times before, and was pretty much alone, but tourism has grown. It remains however an interesting trek, with Lammergeiers still circling the rocky crags above – their main food source being the ubiquitous Pika, a Hamster type creature with a chinking warning call that sounds like a small bird. Lammergeiers have a distinctive diamond shaped tail.

There are larger animals here too, including Ibex, which we saw in a group of three jumping among the rocks. It’s a spectacular animal, and I was surprised to see them relatively tolerant of humans. But global warming has had an impact at Yolin Am. 15 years ago when I first visited, the winter months would freeze the natural spring water (although not the flow) and at one point, a huge glacier type structure about 40 feet high had built up. I climbed it once. Now, it is long gone. In terms of bird life, you can see Black Redstarts, Citrine Wagtails and Snow Buntings here, in addition to Yellow-Billed Coughs. Wild Rhubarb – a silk road traded herb, and indigenous to Mongolia, also grows here. But beware – the Western varietals have had all that bitterness bred out of them. Wild rhubarb – which the Mongolians still use as a medicinal plant to reduce swellings and alleviate stomach upsets. But definitely not as a desert with Custard!

I previously wrote about Yolin Am on this site nine years ago, that report is here.

The Great Mongolian Sand Dunes

The Great Mongolian Sand Dunes, known locally as Khongoryn Els, have built up over millions of years, as the Gobi desert floor particles, whipped up by the wind, hit the high Altai mountains and nestle at the bottom. This s the typical desert scene most people expect when they imagine the Gobi desert, but in reality they only cover 3% of the entire desert. They comprise about 965 square kilometres, extending for about 180km in length and between 2-6km wide. There are several passes through them – but heavier vehicles cannot stop for danger of sinking into them. There is no wadi bashing as in Dubai – the dunes are far too steep. All along the dunes are a variety of camps to stay, with most offering excursions to climb them. That is far harder than it looks. It is also best undertaken in early morning or late evening when it is cooler.

Along large sections of Khongoryn Els runs the Khonggoryn Gol River, which provides a unique ecosystem with marshes and pools of water next to dunes that can reach 300 meters high. They are also sometimes referred to as the ‘singing sands’, as occasionally the wind blowing at the right speed and angle can vibrate the small grains of sand lying along the dune ridges, producing a sound similar to when rubbing your finger along the edge of a wineglass. Sand, which is basically silica, is a main ingredient in glass making.

The herders here use camels instead of horses, although a few still hang around the area. Camel treks are available but beware, camels also attract a specific type of tiny, black sand fly, which can cause irritating bites and are impervious to most repellents if you are staying in a community near them. The answers lie in either using mosquito coils in your ger or tent, or even better, fumigating it completely by burning dried goat or other animal dung instead. Its smoky, but not unpleasant and will drive these annoying insects away. Be sure to secure the ger door or tent flap closed afterwards or they will immediately reinvade.

Another curious insect in this region is the Sand Lion, which are actually the voracious larve of the Lacewing insect. These dig small traps in the sandy ground and wait to feel tell-tale vibrations above. Via a tiny hole at the top of the trap, they then suddenly ambush unsuspecting prey and devour them in their underground lairs…

Immediately after the sand dunes, the Gobi reverts to the ancient Tethys Ocean bed it once was, but stripped back to bare rock and grit. Even so, this can support plants and therefore other elements of life. Any quick walk about will disturb the native lizard, the ‘Toad-Headed Agama’, easily identifiable by the red patch near the head.

Meanwhile, amongst all the desolation, rain clouds begin to gather, and somewhat unusually, it begins to rain. A lonely Demoiselle Crane flies up from the River and flaps his lonely way to further solitude. It is totally silent except for the rare, soft sound of raindrops on the sand.

More ‘Flaming Cliffs’ – Bayanzag

Our next stop was over to Bayanzag, another of the sites visited by Andrews, and also where a great deal of digging was carried out. Here, one really gets the impression of cliffs overlooking a great ocean – now gone. The area is most famous for yielding the first discovery of dinosaur eggs. Other finds in the area include specimens of Velociraptor and eutherian mammals. It exposes rocks of the Djadochta Formation. Standing on top of the cliffs is an area that in the dinosaur era used to be covered in trees, marshes and other prehistoric plant growth, while the waters of the ancient Tethys Ocean washed up against these cliffs. Sea monsters literally used to swim these seas, while terrible creatures maraudered around the lands above. This was the original Jurassic Park.

Tiny white fragments of ancient animals can still occasionally be found amongst the red sandstone, and I have in the past found small fossilized bones, probably of a large species of fish, although not on this occasion.

The nagging wind – which blows hard and hot across these rocks – constantly erodes the sandstone, and one can see its ripples occasionally carved into the surface. This ongoing erosion and the harsh annual weather – from +40 to -40 year round – is consistently breaking this soft rock apart. One year I saw a three foot long, bright white bone sticking out, 30 meters down, exposed as the surrounding sandstone collapsed, leaving the harder fossil behind. It is probably now in the National Dinosaur Museum in Ulaan Baatar.

Some tremendous, as yet unclassified species of dinosaur have also been found here. You will be familiar with the relatively small forearms of the still formidable T-Rex and its Asian cousin, the Tyrannosaurus Baatar.

Here, the forearms only of a similar, as yet unidentified dinosaur have been discovered. They are five times bigger.

The best part, I always thought about the original Jurassic Park film, was the T.Rex chomping down on the parks lawyer. The unidentified monster five time larger could have had an entire laws firms partners for lunch with just one bite, and I am satisfied with the thought. Although these days I suspect I would rather have most politicians meet such a grisly end.

Chapman’s finds, as mentioned, were not just restricted to Dinosaurs. Scuttling fast around their feet, and probably too small and nimble to be considered viable prey, were what were to become the next step on the evolutionary process. While Dinosaurs didn’t fully die out – we can still see some of their close relatives today live on for example in crocodiles and birds – it was the warm blooded mammals who overtook the Dinosaurs as the dominant larger species on earth. One mammal, alive today, even grew larger than the largest Dinosaur, and that is the Blue Whale. I imagine these, which I have seen in the wild off the Sri Lankan coast, swimming through the Tethys Ocean waters. They never did, being an evolutionary step hundreds of millions of years yet to arrive. But the thought of whales gliding through the Oceans is preferable to politicians, and I eject the latter from my mind as a human sub-species preferably doomed to extinction.

The Dinosaur-era mammals, albeit hundreds of millions of years ago, proved resilient and adaptable. So successful was this evolutionary prototype that they still look similar to animals we find today. The Microtherulum, for example, is 120 million years old but looks very similar to today’s tree-shrews and similar creatures. Evolutions basic creed: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Change comes only when necessary.

A Forest In The Desert

As we have seen, there are many different types of Gobi. Another surprising addition are the Saxual Tree Forests, which are endemic to Mongolia and parts of Kazakhstan. Dating back to the times of the Dinosaurs, this ancient species has evolved to extract what I can from what little precipitation there is – and forms quite significant areas of growth.

Obviously, with so little water available, they grow very slowly, meaning the wood is very dense – a piece of Saxual wood will sink in water. They also help colonise parts of the desert – roots holding the sandy soil together enough for burrowing animals – such as the Mongolian Great Gerbil, to survive here. That encourages raptors such as Rough-Legged Buzzards that pry upon them and can be seen wheeling overhead, looking intently for their next meal. These Gerbils are the largest of the Gerbil family, growing up to 20cm long, and are found throughout such habitats. Needless to say they too have keen eyes and at the slightest unexplained movement disappear back into their sandy burrows.

The Saxual Sparrow – only found in these forests – has also managed to adapt and survive in these woods – and has evolved as a highly specialised bird.

While it may look like an ordinary sparrow, it exists only on desert plant seeds, and nests in either the trees, or rocky sandbanks where it can find a niche. Sometimes flocks can be seen, flying very low over the trees before apparently disappearing – 20-30 birds at a time suddenly vanishing into the relative safety of the Saxual Trees foliage. They too are vulnerable to air attacks from birds of prey.

The forests serve in part as a type of refuge for many species, as they provide cover and shelter, while other edible plants also exist among the twisted Saxual tree limbs. However, there are drawbacks – Saxual wood – although it is extremely heavy to lift and very hard to saw – burns hot and long, making it a favourite winter fuel for nomads. That has led to some human encroachment in these remote areas. Happily though, I noticed the government had hived off adjacent, quite sizeable areas and planted Saxual seedlings. It may take many years for them to reach maturity – these trees can live for several hundred years – but the work is underway is protect and encourage these habitats.

Neither are burrows always safe. Even in Mongolia, there are snakes, with several species extant. Some, such as the Halys Pit Viper (Gloydius halys), are venomous. All will eat eggs and young. All have some unique traits in that they hibernate during the frigid winters, so need to stock up on food during the summer and autumn. During hibernation they will utilise old burrows – meaning the Gerbils and birds are constantly on the move in a Saxual Tree version of building new real estate. That evening, a Halys Pit Viper slithered around my Ger. In this region of Mongolia, the internal structure of Gers includes snake-proof, ground level linings to keep them out. With no anti-venom easily available, and the venom known to cause significant pain and potentially lethal, this is one creature best avoided.

The Gobi Horse Milk Dairy

One of the pleasures of trekking the Gobi are the unexpected incidents that occur. While getting admittedly a little lost en route to our next destinations, we happened across a cashmere goat herder – on his motorbike – to ask directions. Leaving his 100 or so goats to wander about on their own – after all, where can they go too? – he directed us to a distant ger for further directions.

These people were dairy producers – of horse and goat milk, which they processed themselves and then resold at the local markets in Mandalgovi. They also made goat and horse milk sweets and cheeses – as well as Airag (Kumis) – fermented mares milk.

Naturally we invited into their ger to have some tea, airag and snacks. The woman of the house was also breast-feeding her third child. The significance of this very mammalian trait would soon become apparent.

After chat and tea, and directions had all been adequately dispensed with – the nomadic herders are always very hospitable, knowing that one day they might need assistance – we were informed that it was to be horse milking time, and that we were free to watch. The mares which have foaled are milked every two hours.

The procedure is to allow the foal to take some of its Mother’s milk first, then remove it from the teat, while keeping it close to the Mother, who thinks that the foal is still suckling. The mare continues to be milked – by hand – with each horse producing about two litres, every two hours. With ten mares (and one happy Stallion) that’s a lot of milk.

Processing it is almost immediate. The ger fireplace is in constant use, and with no available wood to burn in the Gobi Steppes, that ancient, reliable source – dried animal dung – is used instead. Everything is recycled or reused in the Gobi – including poo.

When simmered enough, the milk is canned, stored and sent to market every two days.

Sweets and cheeses are also produced and sold onto the local markets. The cheese is simply dried in the sun on the ger roof.

To produce Airag, that favourite beverage of the nomads, milk is simply whisked by hand several thousand times. It becomes naturally fermented, and tastes slightly salty. The longer airag is left – and especially in the sun – the more alcoholic it becomes. These herders also make a stronger airag – which eventually becomes clearer. A goat-milk vodka. And very good it is too! The Mongolian word of ‘Cheers’ incidentally is the excellent greeting, “Toktoy!”

Dundgovi: The Ongi Monastery

Our next stop was at Dundgovi, basically following the River Els, and to a naturally formed hermitage created by mountain fissures protecting a small valley from the worst of the Gobi winds and sand. The river winds its way through this small area, which has for centuries been recognised as possessing a ‘special energy’.

Here is the central point of the Gobi desert – yet it’s hard to fathom this when surrounded by greenery, water and poplar trees. Not surprisingly, it attracts plenty of wildlife from the big wild Argali sheep to Gazelles, Snow Leopard and Ibex.

Here was also Mongolia’s largest Buddhist monastic settlement, at Ongi, which since the 16th century lived here in relative peace – developing over 200 separate temples and over 1000 attending monks in situ. That tragically changed in 1939 when anti-religious purges under the then Communist Government razed the complex to the ground and massacred many of the priests. It was an act of savage violence in a place of the utmost serene beauty. Fragments of the temples still lie in piles and are scattered all over the ground. For the next 60 years Ongi was nothing but devastated ruins and the cackling, desolate call of windblown crows.

That changed in 2004, when one of the temples, and a solitary stupa were reconstructed. One monk is in residence; he has about ten followers. We paid him a visit, during which he blessed us and had time for a chat.

Ongi is a strange place, yet retains an element of hopeful optimism even amongst its bloody past. That appears in tandem with Buddhism in general. Slightly subdued, but nonetheless buoyed by his blessings to wish us a safe journey home, we begin our long journey back to Ulaan Baatar.

Back To Ulaan Baatar

The next day is a ten hour, mainly off-road drive returning to Ulaan Baatar, with oceans of green returning as the desert steppe gradually gives way to grass steppes, and horses begin to return more frequently to the scenery.

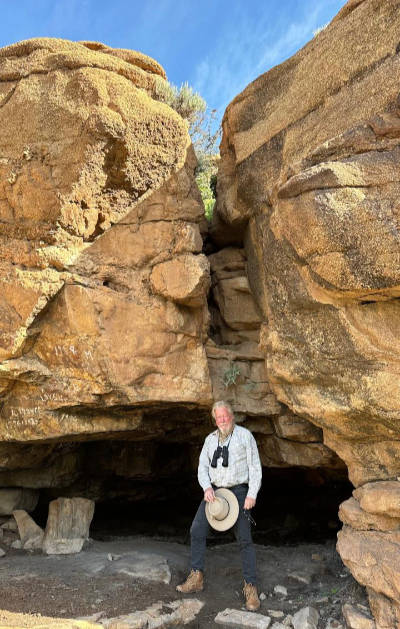

We pass through a rugged, mountainous area that used to be – and probably still is – the haunt of a handful of hardy Buddhist hermits who eked out an existence in the caves deep instead these formations. They stretch, these barren rocks, for over 50km. Much remain unreachable and unexplored.

What the Gobi does tend to impress upon you is the return to a more natural rhythm – largely unencumbered by modern distractions such as email, TV and the internet, life quickly begins to revert to early morning starts and evenings that for me, ended after couple of hours sky gazing. The ‘Night Sky’ app is a useful addition to the spotting of celestial objects.

There have been some improvements in the overall Gobi travelling experience. Much to my surprise – I had previously always avoided them and preferred to stay with passing nomads – the Ger Camp scene has improved. Standards have been set, and such operations now have to be licenced. That means at least clean bedding and a decent meal. The days of oily mattresses and a Goats Head for dinner appear to largely be over, although I retain fond memories.

The Gobi Aimag capital ‘cities’ have boomed, what used to be one horse towns with very basic amenities, now boast populations of 10,000. Supermarkets, small hotels and even local museums have sprung up. With that comes an increase in tourism. The Gobi is not as “off the planet” as it used to be – but it still takes preparation to visit, and the Gobi’s soul will affect your overall life attitude when you return to the city – for the better.

That pang of resentment as our vehicle hit an Ulaan Bataar traffic jam was telling. So was the thought “When will I next return…” A promise, not a question.