I’ve been fortunate this summer to spend a good month with friends of mine who have a Dacha about 100km south from Moscow, on the road to Minsk. Correctly speaking, Dacha’s were summer houses gifted to individuals who had ‘served the State’ – a traditional begun by the Tsar and continued during the Soviet era. Most Dachas today that are in family hands date from the latter period, and are often collective – with owners all having had the same background in the military or with specific factories or organizations. Consequently they are often grouped together in a compound, albeit out in the country, typically near a large lake or river, yet enabling a common and shared security.

I’ve been fortunate this summer to spend a good month with friends of mine who have a Dacha about 100km south from Moscow, on the road to Minsk. Correctly speaking, Dacha’s were summer houses gifted to individuals who had ‘served the State’ – a traditional begun by the Tsar and continued during the Soviet era. Most Dachas today that are in family hands date from the latter period, and are often collective – with owners all having had the same background in the military or with specific factories or organizations. Consequently they are often grouped together in a compound, albeit out in the country, typically near a large lake or river, yet enabling a common and shared security.

Even in Russia today, maybe people leave the big cities during the summer months and head out to their Dacha. Gardens are often overgrown on first arrival, yet hidden treasures soon appear – the cucumber patch, herb garden, and tomatoes are all reclaimed, while Rose Bushes trimmed, other garden flowers tidied up and stock taken of the Fruit Trees – Cherry, Apple, Pear… the fireplace will be cleaned, and stacks of firewood will be procured to warm the house up after what has often been a long winter of disuse. Blankets aired, bedding washed and hung to dry as Russians all over the country prepare for their annual two-three months of Tolstoyic idyll.

I too, don a smock, and spend hours sorting out, coring and cleaning apples. Fresh Milk, cream and butter (and occasionally more) are purchased from the local Orthodox Church, who have enough lands and charitable resources to maintain a herd of cattle year round. It is not uncommon in these parts for the Church to have a Dairy building alongside and to smell of incense and cream. I fish the local pond, and catch small Dace and the occasional Perch. They are delicious fried.

Then we come to the serious business of the Samovar. I am keen to learn its mysteries. Soviet era improvements saw the invention of the electric samovar. But that’s not a real samovar, it’s an electric kettle in the shape of a samovar. A real Samovar needs to be fired up. Here, I begin to learn that the best fuel to use are pine cones. Most Westerners think Samovars are wood burning – not true. Pine cones are the best, and with a good clean of the grating at the bottom, I pop a couple inside the central flue and light them with the aid of some dried grass, and a small amount of kindling. Here I learn another use for the Galosh. Rather than trying to blow down the central tube, one needs to encourage air and combustion up. Sticking one Galosh over the top and ‘pumping’ it to aerate the smouldering embers at the bottom of the tube works. One then adds more pine cones, and the result will be a brilliantly smoking, steaming Samovar Pipe. It looks excellent, almost like a steam engine. The complete Samovar will have an attachment on top of the pipe; that is to balance a kettle on. Or hot water can be drained off from the main tap. And here’s the reasoning behind the use of Pine Cones and not wood, and the need to use natural methods to get the fire burning – the water takes on some of the taste of the Pine. I guess it’s just the general smokiness of the thing, because the water compartment is obviously separate from the fire. Yet tea made with water brewed in a samovar fuelled with pine cones just tastes different. It’s a phenomena I’ve tried elsewhere – firing up a samovar at my home in Sri Lanka I have used different fuels, most notably with dried coconut husks (there being no pine trees at the tropical south coast) which provided a slight sweetness to the water. The same with discarded cinnamon twigs and even clippings from tea bushes. So the fuel is important to the quality of water. Don’t just use wood. Pine Cones are ideal and the original fuel, or one can adapt according to where you live. Now my friends up the Sri Lanka’s highlands, also want a Samovar, and they do have pine trees up there.

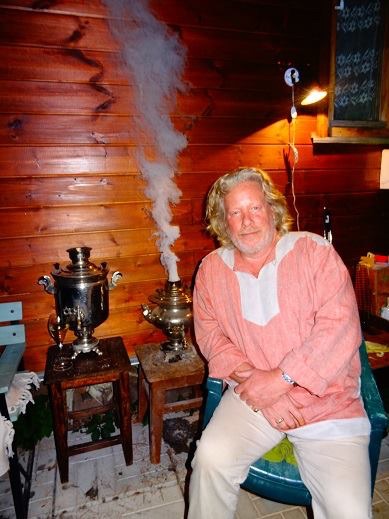

My samovar fired up in Sri Lanka, using dried coconut shells as fuel. The water tastes sweet as a result

Finally, a word on Russian tea drinking. This is not the rather soppy English milk and sugar variation. Tea was first introduced to Russia through the Silk Road, centuries ago, through the overland routes. Apparently that journey would take six months. Every evening, the Caravan would stop to camp, light fires, eat and rest. Over time, the packed tea took on a slightly smoked flavour as a result, and even today Russian Karavanskaya Tea can be found in shops across the country. It’s a little like the smokey flavor of Lapsang Souchong. The Russians also like to flavor their tea with dried fruits, flowers, herbs, or lemon, and use long crystal or glass cups known as Kolchugino, placed in silver tea holders to drink it with. The Russians are huge tea drinkers, and the art of using a Samovar a vital part to it. It is a skill I am very pleased to have learned.