When tracing back the historical background to the production of wine, some of the earliest examples, both in terms of archaeological findings and the written word, hark back to Georgia, in the Caucasus region, and the Qvevri method. I enjoy big tannic reds, and am curious to learn how the extra tannins imparted during the Qvevri process will affect this ancient, and traditional winemaking technique.

When tracing back the historical background to the production of wine, some of the earliest examples, both in terms of archaeological findings and the written word, hark back to Georgia, in the Caucasus region, and the Qvevri method. I enjoy big tannic reds, and am curious to learn how the extra tannins imparted during the Qvevri process will affect this ancient, and traditional winemaking technique.

These wines are made in a totally different manner to the techniques typically used today. Qvevri are huge, terracotta jars – easily big enough to fit a man inside, which, once fired, are buried in the ground to their necks. To use them, a solution of lime is used to disinfect the interior, which are then completely sealed with beeswax. At harvest, the grapes are thrown in – complete with stalks, and occasionally leaves. These lees are left for three-four weeks, and stirred regularly. The stalks, sediment and lees are then removed, the Qvevri topped up with previous years vintage, then sealed tight, again with beeswax. They are then vintaged, and have been known in the past to have kept, undisturbed for fifty and even 100 years.

I am in Tblisi, visiting my good friend Simon, to learn more about Qvevri wines and tour some of the vineyards.

I am in Tblisi, visiting my good friend Simon, to learn more about Qvevri wines and tour some of the vineyards.

A major factor in the success of this wine region is the location, with the best vineyards being in the Kakheti Valley, watered by the Alazani River, sun drenched by its sub tropical location east of the Black Sea, and cooled by the huge Caucasus Mountains.

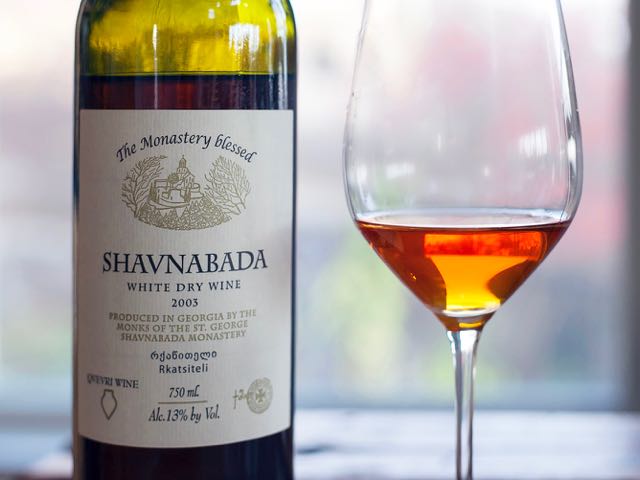

The grape varietals are different here too, and almost unknown in Western Europe, yet long regarded in Eastern Europe, and in some cases, right across Central Asia. These include the reds Aleksandrouli, reputed to have originated from the legendary Muscats of Alexandria, Mujuretuli and Saperavi, the ancestor of Cabernet Sauvignon. I think Saperavi is an excellent grape, it makes good, hearty, full bodied wines, and can be found extensively in Eastern European countries. Given the end of World War Two and the raising of the Iron Curtain it has not been part of Western European wine drinking for over 70 years, but is well overdue a renaissance. If you think of it as Cabernet Sauvignon’s older, more experienced and interesting brother, you’ll get a decent idea of how the grape performs. White varietals here include Mtsvane; Rkatsiteli one of the easts most prized wine grapes, and Tsolikouri, long a favorite of Russian nobility. These are serious wines, with an ancient pedigree stretching back millenia. They are revered in Georgia, as is the Vine itself, one of the most famous Saints in Georgia, St. Nino is often depicted with her hair braided in vine leaves, while the Orthodox symbol in Georgia is a cross made from two bound vine stems. Wine infuses the entire culture – even Monasteries have vineyards within their grounds.

The grape varietals are different here too, and almost unknown in Western Europe, yet long regarded in Eastern Europe, and in some cases, right across Central Asia. These include the reds Aleksandrouli, reputed to have originated from the legendary Muscats of Alexandria, Mujuretuli and Saperavi, the ancestor of Cabernet Sauvignon. I think Saperavi is an excellent grape, it makes good, hearty, full bodied wines, and can be found extensively in Eastern European countries. Given the end of World War Two and the raising of the Iron Curtain it has not been part of Western European wine drinking for over 70 years, but is well overdue a renaissance. If you think of it as Cabernet Sauvignon’s older, more experienced and interesting brother, you’ll get a decent idea of how the grape performs. White varietals here include Mtsvane; Rkatsiteli one of the easts most prized wine grapes, and Tsolikouri, long a favorite of Russian nobility. These are serious wines, with an ancient pedigree stretching back millenia. They are revered in Georgia, as is the Vine itself, one of the most famous Saints in Georgia, St. Nino is often depicted with her hair braided in vine leaves, while the Orthodox symbol in Georgia is a cross made from two bound vine stems. Wine infuses the entire culture – even Monasteries have vineyards within their grounds.

So what are the wines like? Firstly, lets see what happens to the Lees, the twigs and leaves and other flotsam that gets raked off the top of the Qvevri after a few weeks macerating. Brilliantly, that is distilled, and turned into a Georgian Grappa style white spirit known as Chacha. It is very strong, and not for the faint hearted, although on a cold morning I will add it to coffee. There are in fact also some very good Georgian Brandies, and if you see any Sarajishvili on your travels, they are well worth picking up.

So what are the wines like? Firstly, lets see what happens to the Lees, the twigs and leaves and other flotsam that gets raked off the top of the Qvevri after a few weeks macerating. Brilliantly, that is distilled, and turned into a Georgian Grappa style white spirit known as Chacha. It is very strong, and not for the faint hearted, although on a cold morning I will add it to coffee. There are in fact also some very good Georgian Brandies, and if you see any Sarajishvili on your travels, they are well worth picking up.

But back to the Qvevri wines. They can be something of an acquired taste, however if you enjoy full bodied, tannic wines, you’ll like Qvevri’s. Interestingly its the whites that are the best – grapes such as Rkatsiteli especially can take on a lot of tannin and end up being full bodied whites. They also develop an intense orange colour.

These wines work perfectly well on their own – and they really don’t need much chilling. Alternatively, they are excellent with many dishes involving cheese, and are good with kebabs, pork as well as meatier fish dishes such as smoked sturgeon and so on. Most qvevri wines are in fact of white grape varietals.

These wines work perfectly well on their own – and they really don’t need much chilling. Alternatively, they are excellent with many dishes involving cheese, and are good with kebabs, pork as well as meatier fish dishes such as smoked sturgeon and so on. Most qvevri wines are in fact of white grape varietals.

Of the reds, Georgia tends to use its Saperavi and other reds as “French” style wines, and not use them in Qvevri’s, although this was the original method. If you can find Qvevri reds, they are often described as “black” wines as they contain so much additional tannin for being left on lees for so long. These are very much an acquired taste, although producers are now attempting to feed demand by producing red qvevri wines having left them on lees for just one or two weeks rather than longer periods. These can also be excellent, and very good with heartier meat dishes such as beef.

Simon and I spend several days touring a variety of vineyards, and enjoying the rare and extraordinary variety of Qvevri wines on offer. I am so taken I intend to regularly invest in cases as part of my wine cellar.

Simon and I spend several days touring a variety of vineyards, and enjoying the rare and extraordinary variety of Qvevri wines on offer. I am so taken I intend to regularly invest in cases as part of my wine cellar.

But for now, this excursion into one of the worlds most interesting, as yet unexplored, yet historic, and excellent wine regions has been very fruitful indeed.

But for now, this excursion into one of the worlds most interesting, as yet unexplored, yet historic, and excellent wine regions has been very fruitful indeed.

Gaumarjos!